In the kind of company that Simon Fraser University's Continuing Studies in Science department tends to bring together to talk about salmon, it is no small challenge for me to find something useful to say. Surrounded by so many people who know salmon better than I do, it's impossible not to feel as though, at best, I would be telling people things that they already know, and know much better than I do. And I don't think that I could simply read from something I have written about salmon, because on the centenary of the birth of Roderick Haig-Brown, and to be in Campbell River, his beloved home town, I could only feel as though I were trespassing upon the work of a truly great writer, on his home ground.

What I thought I would do is to talk a bit about Haig-Brown's conservation concerns in their contemporary, global context, and the global relevance of the effort that has been at the centre of attention – the implementation of the Wild Salmon Policy – and why, especially as Canadians and British Columbians, it matters that we get it right.

It matters, not just to answer to the question that Brian Riddell, who is here with us tonight, asked directly and forthrightly in his seminal 1993 paper:

Spatial Organization of Pacific Salmonids: What to conserve? It matters, for starters, because of Canada's international commitments under a variety of international covenants, not least the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. It matters because the world matters, and the question, "What to Conserve?" is a global challenge that humanity faces now as never before.

And so I thought that if I was going to make some use of myself, I would address some major trends in the way that question is being confronted globally, and the way Canadians, and British Columbians, are involved in that difficult and necessary work.

Everything Is Connected. We Are All Related.Since this is all about the interconnectedness of things, I thought I'd start with some recent events that are directly implicated in these emerging approaches to the question - "What to Conserve?" These events will appear to be not only unrelated to one another, but also unrelated to that question, when in fact they are indeed closely related, and they raise the question directly, and the work of fulfilling the promise of the Wild Salmon Policy is also related to these events:

• This past January, at an especially solemn funeral at the St. Innocent Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Anchorage, Alaska, friends and relatives gathered to bid their last farewell to Marie Smith Jones, a beloved matriarch of her community. She was 89.

• In May, 2007, a cavalry of the Janjaweed - the notorious Sudanese militia that has subjected the indigenous people of Darfur to a "slow genocide" in recent years – made its way across the border into neighboring Chad. This time, they weren't after people. They were after the contents of a locked storeroom in Zakouma National Park.

• Around the same time, a wave of mysterious frog disappearances that had been confounding herpetologists from Australia to Central America showed up in the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

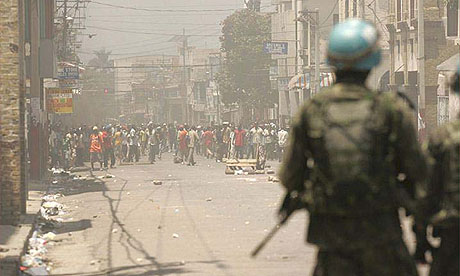

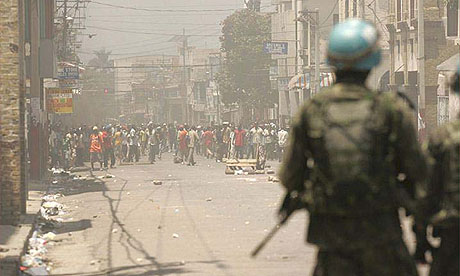

• A year later, in the Haitian capital of Port-Au- Prince, a United Nations soldier was shot and killed during a food riot.

Here's how these events are connected. They are outbreaks, you could say, of an epidemic that is sweeping the world. It has no name. There has never been anything like it in human history. It carries away an entire human language every two weeks. It destroys a domesticated food-crop variety every six hours. Every few minutes, it kills off a whole species.

For all its virtues, environmentalism hasn't made much of a noticeable contribution to its containment, or even to task of adequately describing the phenomenon. On May 16, the Zoological Society of London released an analysis suggesting that since contemporary environmentalism emerged with the declaration of the first Earth Day in 1970, close to one third of all the wild species on earth have disappeared.

Whatever name we might want to give the epidemic, it is a destroyer of worlds. Wherever its shadow falls, it leaves everything monochromatic, monocultural, standardized, and increasingly vulnerable to collapse and disorder. It is bleeding away the wealth and diversity of the human experience, in the same way we have seen the wealth and diversity of the west coast's salmon runs, and salmon fisheries, bleeding away.

It is eroding the resilience of human and ecological systems, and obliterating their capacity to sustain shocks and disruptions. It is causing vast and ancient storehouses of accumulated knowledge to vanish into thin air.

Here are the specific elements that connect these seemingly unrelated events.

In her casket in Anchorage, Marie Smith Jones was the last fluent speaker of the Eyak language. Of the world's roughly 6,800 languages, fully half – some say more like 90 per cent – should be expected to disappear before the end of the century.

As globalized trade expands across horizons, local cultures are undermined and uprooted, and an array of threats present themselves to vulnerable species of animals and plants. If it's not the trade in rare birds, tiger bones or bracelets made from the shells of endangered turtles, it's the trafficking in such exotic commodities as elephant tusks. That's what those Janjaweed horsemen were after in that cross-border raid into Chad. They were after 1.5 tons of ivory worth nearly $1.5 million that park rangers had confiscated from poachers over the years.

In just one of globalization's side-effects, about half of all the endangered species in the United States are in peril because of other species, recently arrived from afar. Some have come as unwanted passengers in the holds of ships. Others came hundreds of years ago, in the form of herds of cattle. Many of these world travelers are microscopic.

The culprit behind the vanishing of so many of the world's frog populations is a fungus,

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, native to southern Africa. Frogs that have evolved alongside it can handle its ravages, but frogs elsewhere are not so lucky. Over the years, the fungus has found its way, via such routes as the overseas trade in frog's legs, to Central America, South America, Australia, and now the United States.

The food riot in Haiti, meanwhile, was just one of several such incidents that erupted around the same time in Yemen, West Bengal, Egypt, Senegal, and elsewhere.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, three-quarters of the world's critically-important food crop varieties disappeared during the 20th century. Hundreds of locally-adapted livestock breeds are also on the brink of extinction. Addressing the world's worst food crisis in a generation, on May 19, in Rome, Alexander Müller, Assistant Director-General the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization, warned that most of the world's food supply had narrowed to just a dozen crops and fourteen animal species.

Globalization, like environmentalism, is not without its own virtues. It is only because of the rapid expansion of globalized trade that we have seen nearly 400 million people rise out of abject poverty in recent years. But what it has also meant is rapid human population growth and the even more rapid overharvesting of natural resources. It has meant crop failure and desertification, and a worldwide food system that demands ever-greater standardization and uniformity.

The work at the heart of the Wild Salmon Policy – the work of answering the question, "What to Conserve?" in the face of globalization – now involves scientists and practitioners from a wide range of academic disciplines and policy areas who have been very busy, connecting the dots, and tracing the myriad relationships between the ethnosphere and the biosphere.

Beyond Mere Globalization, Beyond Mere Environmentalism.

A new kind of conversation has been emerging from this transdisciplinary work, and it is approaching a new paradigm, revolving around the notion of "biocultural diversity." It's showing up in ethnolingustics, cultural anthropology, ethnoecology, and so on, and it has outgrown environmentalism, precisely because it cuts across nature and culture, natural selection and artificial selection, language and landscape.

Last October's Global Outlook 4 report, published by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), reflects the new thinking that is arising from observations of the global crisis in biological diversity. The report reiterated the consensus that humans are ultimately to blame for the current global extinction event, but UNEP made an explicit connection between the ongoing collapse of biological diversity and the rapid, global-scale withering of cultural and linguistic diversity, noting that "cultural diversity is being rapidly lost, in parallel to biological diversity, and largely in response to the same drivers."

For countless millennia, culture has determined nature, nature has determined culture, and the dialectic engages wild and domesticated plants and animals, languages, "traditional ecological knowledge," and systems of resource use that adapt and evolve over time. But globalization is causing these patterns to change rapidly, and to break down. The Global Outlook report notes: "Global social and economic change is driving the loss of biodiversity and disrupting local ways of life by promoting cultural assimilation and homogenization." Further, "loss of cultural and spiritual values, languages, and traditional knowledge and practices, is a driver that can cause increasing pressures on biodiversity. . . In turn, these pressures impact human well-being."

Just one reason these perturbations tend to be so intimately related is evident from just one glance at global map developed in 2003 by the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. It shows that the world's deepest reservoirs of linguistic diversity almost always occupy exactly the same spaces as the world's centres of biological diversity. And a map of the world's deepest reservoirs of biodiversity looks eerily similar to a world atlas showing the centres of domesticated food-crop diversity.

As British Columbians, we don't have to look far, in space or in time, to see the "drivers" behind system collapse.

In 1995, Ecotrust and Conservation International produced a map showing the loss, over time, of the North America's great northwest temperate rain forests, with Campbell River almost at its centre. The map also displayed the status of tribal languages in those forests, over the same period. What the two data sets produce is exactly the same map. But it's important to remember that cause-and-effect lines don't always run in the same direction. It is not always so simple a matter of deforestation leading to species extinction and language death.

Another close-to-home case demonstrates these intimate connections, with the cause-and-effect line running in the other direction, and that's the case of the mountain pine beetle - the most catastrophic insect infestation in the history of North American forests. We've lost about seven million hectares of British Columbia's interior pine forests to the beetle over the past ten years or so, but that story really begins with smallpox, a virus that decimated the interior tribes about 150 years ago. In this case, the people were felled first, leading to the vanishing of healthy forests.

Without Its Forest, A People Dies; Without Its People, A Forest Dies.

It happened this way: Tribal communities practiced a sort of management, thinning the forests by regular burning, which produces more abundant berry crops and mule deer habitat. With the people gone, the eventual result was a landscape of bug-prone, dense forest, and even-aged stands of pine. Exacerbated by modern fire suppression policy, all it took was a minor shift in the climate regime to produce a catastrophic perturbation: fewer winter cold-snaps kept the beetles under control, and the pine forests ended up prey to killing insect infestations.

Making these connections, and the emergence of a deeper understanding of the relationships between biological diversity and cultural diversity (as evidenced by the UNEP Global Outlook Report) should be expected to have significant implications in the way the world answers the question "What To Conserve?"

This new thinking concerns itself with the triangular relationships between linguistic, cultural and biological diversity, which anyone familiar with the history of human beings and salmon on this coast will deeply appreciate. The idea is finally starting to catch on: Language, culture and living things are intimately related, they're each threatened by the same forces, and the contest poses dramatic implications for the future of all life on earth.

Recognizing this, more than 300 leading thinkers in nature conservation, linguistics, anthropology, and biology gathered this past spring at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The museum's Center for Biodiversity and Conservation hosted a four-day symposium, titled "Sustaining Cultural and Biological Diversity in a Rapidly Changing World: Lessons for Global Policy." The symposium concluded with a resolution to be put before the upcoming world congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature - the world’s major environmental network, with more than 1,000 government and non-government member organizations in more than 160 countries.

The motion calls on the IUCN to get with UNEP's Global Outlook program and proceed to integrate culture and cultural diversity in the IUCN's policies and work programs. This is a very big deal. The IUCN has concentrated almost exclusively on ecological health, serving as the world's primary source of data on the status of animal and plant species. Whether or not the symposium resolution is adopted, the fact that it will be debated at all indicates a huge change in the way the world approaches the "What to Conserve?" question.

So that's one of the major trends I wanted to address.

Another involves the challenge of understanding what UNEP calls the "drivers" behind the loss of cultural and biological diversity – the processes that cause things to fall apart, and the forces that put them back together again. This is a primary concern of another new transdisciplinary field, commonly called resilience science. This is a highly theoretical realm of ideas, and while it involves different terminologies than you'll hear in the "biocultural diversity" conversation, the participants are sometimes the same people.

The Unity In Diversity Comes From Structural Resilience. Resilience theory emphasizes the adaptive capacity of what it calls social-ecological systems, and it applies itself to everything from sheep rangeland management in Australia to Caribbean coral reefs. Resilience theory has its own global network - the Resilience Alliance - and it brings together academics from disciplines as diverse as biology, physics, and economics. It publishes its own scientific journal, Ecology and Society.

The Resilience Alliance is changing paradigms all by itself, and it's also been attracting a lot of attention lately. Just two weeks before the symposium in New York this year, more than 600 scientists, policy makers, and artists, even, were attending the Resilience Alliance conference in Stockholm.

It is worthwhile noting the contribution that Canada and Canadians, and British Columbians, are making in these emerging fields.

Resilience theory is most closely associated with the renowned ecologist Crawford "Buzz" Holling, the 2008 recipient of the prestigious $250,000 Volvo Environment Prize, who lives just down the highway, in Nanaimo. One of the pioneers in the study of "biocultural diversity" is also a British Columbian. Luisa Maffi, a key contributor to the biodiversity sections of last year's UNEP Global Outlook report, is an Italian-born linguist and anthropologist who lives on Saltspring Island.

Further, Canada played a key role in an important milestone in the growing acceptance of the global importance of protecting cultural diversity in December, 2006, with the UNESCO-brokered international treaty on cultural rights (British Columbians played a key role in that effort, too, perhaps most notably the publisher Scott McIntyre).

UNESCO specifically describes the purpose of the treaty as an effort to protect the diversity of cultural expressions from "the dangers of globalization." The treaty keeps national cultural policies free from the usual anti-protectionist prohibitions contained in free-trade deals.

Another milestone in which Canada played a crucial role was the UN General Assembly's 2007 confirmation of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Canadian diplomats fought long and hard for that declaration, over a dozen years, and while Canada strangely ended up voting against it at the UN Human Rights Council level, at least it was ultimately adopted.

One thing I think is important to acknowledge in these developments is that environmentalists have also taken a long time to wake up to the importance of making the connections between nature and culture. Environmentalists have tended to see only pristine wilderness in ecosystems that we now understand to have been in fact transformed, and in some cases radically reshaped, by New World peoples.

This is especially important to consider in the matter of salmon ecosystems and the ancient peoples of this coast. One would be hard pressed to identify a single significant population of salmon - or a "conservation unit," to borrow the terminology of the Wild Salmon Policy – that has not been subjected to major human harvest (and perhaps the term "management" would not go too far) since the Early Holocene.

We are only now coming to appreciate the implications of that smallpox-induced collapse in the relationship between aboriginal societies and pine forests. What implications remain unconsidered in the ancient relationships between aboriginal societies and salmon? We know the extent to which salmon gave shape and form to aboriginal civilization. But what do we know of the degree to which aboriginal people gave shape and form to the abundance and diversity of salmon?

And what are the implications of allowing habitat loss, overfishing and other anthropogenic effects to sever the ancient relationship between the diverse aboriginal cultures of this province and the astonishingly diverse salmon populations that sustained their cultures from time out of mind?

This is not to say that there are no implications for British Columbia's settler cultures that are at stake. There are, and we are most fortunate in this respect, in that there is a deep and abiding affection for salmon among Canadians, and among British Columbians, especially.

Time and again, we have shown that, despite our political leadership, as individuals and as communities we are willing to make whatever sacrifices are necessary to conserve salmon, to share the landscape with salmon. Because this is what we want, as a people, then flourishing salmon runs that we may then bequeath to those that come after us constitute an entitlement, as people of a free and democratic society.

"Freedom To Live Fully The Life That Is Before Them." There are also global implications that arise in the extent to which Canada, one of the most resource-rich and sparsely-populated countries in the world, adequately protects the abundance of diversity of the salmon runs of this coast. Everything really is connected. If we can't live up to our international obligations, we are in no position to hector such nation states as China, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia – where some of the deepest reservoirs of biological and cultural diversity on earth are found – about living up to their obligations.

That is just one reason why all of us must work so diligently to fulfill the promise of the Wild Salmon Policy. And here, I will leave it to Roderick Haig Brown to make the point, more eloquently than I could, from his beautiful collection of essays called

Measure of the Year, first published in 1950:

Again it is a matter for the voices and thoughts of families and individuals, breaking through somehow, anyhow, to express that only wish of decent men everywhere: freedom to live fully the life that is before them, according to their individual consciences, and without hurt to others. If the wisdom of small nations can be spoken with weight that matches the power of the great nations, there will be some hope.