Amazing, appalling, arcane = anti-fascist.

My essay on the Canada and the New Internationalism, published over here last week under the headline “Reinventing Diplomacy,” has set off a bit of a row. Among the letters is a particularly amusing one from a leading Vancouver anti-war-committee-goer, who is both “amazed” and “appalled” with me. He says the UN's "responsibility to protect" doctrine, the Ottawa Landmines Convention, the International Criminal Court and the Convention on Cultural Diversity are just attempts to "put a human face on objectionable political projects, particularly in the international sphere." Or something like that. I could be wrong. It's hard to say.

My essay on the Canada and the New Internationalism, published over here last week under the headline “Reinventing Diplomacy,” has set off a bit of a row. Among the letters is a particularly amusing one from a leading Vancouver anti-war-committee-goer, who is both “amazed” and “appalled” with me. He says the UN's "responsibility to protect" doctrine, the Ottawa Landmines Convention, the International Criminal Court and the Convention on Cultural Diversity are just attempts to "put a human face on objectionable political projects, particularly in the international sphere." Or something like that. I could be wrong. It's hard to say.(I hope these people save some of their vitriol for my dear friend and fellow islander Grant Buday, whose review of Jasper Becker’s Rogue Regime describes Hero of the People and Dear Leader Kim Jong Il as “a short man who resembles a toad in a toupee.” They should surely be amazed and appalled at that slight. And perhaps compelled to write more letters.)

But the complaints about "Reinventing Diplomacy" have not been universally frivolous. The nationalist Robin Matthews (Treason of the Intellectuals; The Death of Socialism and Other Poems) takes me to task on the Vive le Canada webzine for my “very strange reading” of Canada’s emerging muscularity in global politics. I think Robin’s got it wrong. But of course I would say that.

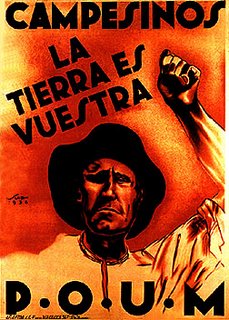

The debate in play here, while a bit marginal in the clichéd “broader scheme of things,” is actually quite closely related to a very turbulent current of contemporary controversy. Last September, the British “pro-liberation” leftist Harry Hatchett (see my link to Harry's Place at the side, under "Brits") described that controversy this way: “Of course the left has always had its splits, divisions and in-fights and if we look back to the Spanish civil war there was certainly no love lost between the Anarchists, the Trotskyists and (Stalin's) Communists. But the difference with today is that back in the time when the International Brigades were fighting fascism in Spain, no-one on the left actually urged support for Franco.”

Meaning, you should gather, that nowadays you can find British pop-culture pseudosocialist George Galloway (who is arguably some sort of Mosleyite anyway) slobbering on Syrian president Bashar Al-Assad's slippers, and a “peace movement” weirdly quiet about Iran’s holocaust-denying president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, with his covetousness for nuclear weapons and all, and throngs of protestors going all where-have-all-the-flowers-gone about the overthrow of the Taliban. That kind of thing.

Here’s how I tried to express similarly amazing and appalling ideas this week, in response to Robin Mathews, on Vive le Canada:

As the author the essay ("Reinventing Diplomacy", Georgia Straight, 12-Jan-2006) that my friend Robin Mathews critiques in his thoughtful column here, I thought I would take the liberty of responding to some of Robin's points, and raising one or two of my own.

Robin writes: "For some arcane reason, Glavin wants us to believe the `new internationalism defies old left-right clichés'. He writes that the new ideas `defy the conventional categories of left and right in global politics'. That is, with respect, a very strange reading. . . that the left/right conflict is somehow no longer present, or is fading."

First, I should point out that Robin has read rather more than I intended into my essay, in some respects, and less, in others.

I most certainly do not argue that the left/right conflict is "somehow no longer present" in the development of independent Canadian foreign policy or military policy. Robin sufficiently resolves any doubt about the Canadian foreign-policy posture associated with the "right" by mere reference to the Conservative Party's foreign affairs critic - the Bible fetishist, creationist and homophobe Stockwell Day.

But the "right" in this country at the moment is, I'm afraid, quite different than anything we are used to. It is an alliance of American-inspired neoconservatives on the one hand and the Canadian adherents of those exotic, cargo-cult American folk religions (usually described generically as "evangelicals") on the other. Led by Stephen Harper, they have captured the infrastructure and command of Canada's venerable old Conservative Party. These people despise the conservative values and the politics of conventional Canadian toryism. They are completely outside the traditional Canadian consensus among and between tories, liberals, social democrats and socialists. Their politics are American.

Meanwhile, the liberal internationalism that Canada has pioneered in recent years, against the consistent and vigorous opposition of the United States, is quite robust enough to embrace ideas that lie across the spectrum of Canadian toryism, liberalism, social democracy and socialism. But there is an American-influenced "left" in play in Canada, as well - the neoconservatives' opposite. That "left" opposes the new diplomacy for its own, usually incoherent "counterculture" reasons. The tendency is almost universally opposed to the more robust assertions of the "new diplomacy" when it requires critical, armed Canadian solidarity with democratic forces in the failed states of Afghanistan and Haiti.

I am unapologetically of the "left," but I do not recognize the hard-line "troops out" crowd as my comrades on these questions. In coming to terms with the way Canada should discharge its duty of solidarity with the people of Afghanistan, for instance, I am much more interested in what the people of Afghanistan have to say on the subject than in what George Galloway, Noam Chomsky, Cindy Sheehan or any other British or American demi-celebrity has to say.

I'm interested in what people from Canada's young and progressive Afghan community have to say. And these people say, quite emphatically, and overwhelmingly, "stay the course."

It was the Afghan Women's Network that first cried out for Canada and our NATO allies to move into Kandahar, where Canadian troops are now temporarily engaged alongside American forces in a hill-by-hill rout of the fascist remnants of the Taliban. I am not at all ashamed that we have heeded that call.

The Canadian Forces should be there, and the fact that the Yanks are there too is completely immaterial to the question of whether Canada's soldiers should be engaged there.

In that respect, Canada's role in Haiti is similar. There may be many worthwhile and necessary questions to be raised about the effectiveness of Canada's role in Haiti, but running away from Haiti is simply not on. In English Canada, the left appears content to accept an American-style "troops out" posture with regards to Haiti. In Quebec, "the left" is less susceptible to the practice of adopting American counterculture postures without scrutiny. The Quebec "left" is fully engaged with Canada's UN-sanctioned mission in Haiti, which enjoys the support of the Liberal Party (obviously), the Bloc Quebecois (enthusiastically), the New Democratic Party (fitfully) and Quebec's trade unions, civil rights activists and feminists.

It is in these ways that the "new internationalism" doesn't fit neatly within the standard "left-right" analyses of developing-world solidarity, international law, or national sovereignty.

As for me, I see no reason to engage in those elaborate circumlocutions necessary to the work of characterizing Canada as an "imperialist" power in either Haiti or Afghanistan. To find the historical roots of Canada's missions in Afghanistan or Haiti, I do not rummage around in the clippings files related to the abominable U.S. expeditions in Vietnam, El Salvador, Nicaragua or elsewhere. I see the origins of Canada's engagement in Afghanistan and Haiti in the armed struggle waged by Canada's Mackenzie-Papineau battalion against the fascists in Spain, during the 1930s.

On Sunday, Glyn Berry - a progressive, an ardent champion of the "new diplomacy," a senior Canadian diplomat, and a loyal comrade of the Afghan people - was murdered near Kandahar. He died in a Taliban-orchestrated suicide-bomb attack, which also killed two other civilians and wounded three Canadian soldiers.

A couple of years ago, here's what Berry had to say about the duties of solidarity that progressive people everywhere owe to one another: “In today's world, sovereignty is no longer exclusively about rights, it is about responsibilities. The primary responsibility of a government to protect its own people is integral to the very concept of sovereignty. When that responsibility is not or cannot be exercised in the face of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, including ethnic cleansing, there can be no realistic option but for the international community to take collective action, including, as a last resort, the use of force. . .”

Of course it would be nice if this solemn responsibility could be discharged by having Canadian soldiers in blue berets wander around the bazaars of Kabul passing out packages of sweets to children. But sadly, in order to engage in peace building, militia-demobilization, well-drilling, landmine clearance, school construction, vote-tallying, and hospital building, you sometimes first have to kill some fascists.

Oh well.

Robin raises some very important questions about the implications of Canada's new muscle-flexing in world affairs vis-à-vis the United States and the various global designs and ambitions the U.S. is pursuing. These are important questions, and Vive Le Canada readers are well served to pay attention to the questions Robin is raising.

But for me, and I believe for the "left," at the end of the day the fundamental questions are fairly straightforward: Could we really have allowed the complete collapse of order in Haiti because of some reactionary preoccupation with nation-state "sovereignty"? In Afghanistan, are we with the fascist thugs who would throw acid in the faces of unveiled women, or are we with the democratic forces of Afghanistan, the women of Afghanistan, the people of Afghanistan?

I think the answers to both those questions are clear.

In Solidarity, Terry Glavin.

Meanwhile, for a solid primer on the questions that arise in any sensible discussion about these sorts of things, you should have a look at Norm Geras' excellent essay on Larry May's Crimes Against Humanity: A Normative Account in the recent issue of Democratiya, here.

1 Comments:

During the Waffle debates of the early 1970's, Robin Matthews took it upon himself to try and have any professor working in a Canadian university who happened to be an American citizen fired on the grounds that all American citizens are "cultural imperialists" who play a role in perpetuating Canada's status as a colony enslaved by American imperialist interests. Later, Matthews took jobs in US universities while maintaining his view that all US born professors teaching in Canada must be fired.

In a 4th year undergrad course he taught at SFU, Matthews averred that Canadian philosophers alone resolved the "subject-object divide". Sure Robin.

In his highly original titled book 'Treason of the Intellectuals", Matthews attacked Esther DeLisle's thesis on antisemitism in the Quebec of the 1930's and 40's, but when I asked him about some of his criticisms he admitted he had never read her thesis.

Treason of the Intellectuals, Robin?

Robin Matthews is a kooky ultranationalist and a flake.

Post a Comment

<< Home